PE Emulation With Code Coverage Using Qiling and Dragon Dance

Qiling Emulation

The Qiling emulation framework was built with the goal of emulating shellcode from various operating systems due to the ever-increasing amount of complexity of shellcode, as xwings stated in his talk at ZeroNights 2019. The framework, however, evolved into a binary instrumentation and binary emulation framework that supports cross-platform and multi-architecture where multiple architectures (such as ARM and x86), operating systems (such as Windows and Linux) and file formats for loading binary code (such as ELF and Portable Executables) are supported.

Portable Executable Code Coverage

While looking at ways to contribute and improve coverage for the Windows operating system APIs it has been difficult to trace execution flow within a binary that is calling specific APIs that I would like to emulate. Fortunately, @assaf_carlsbad submitted a PR which would do exactly this with DRCOV-compatible code coverage collection. This, however, was limited to the Portable Executable UEFI loader, so I decided to add support for the Windows Portable Executable loader with the following changes:

diff --git a/qiling/loader/pe.py b/qiling/loader/pe.py

index b6e46c8e..3375bbf2 100644

--- a/qiling/loader/pe.py

+++ b/qiling/loader/pe.py

@@ -87,15 +87,20 @@ class Process():

self.ql.nprint("[+] Cached %s" % path)

dll_base = self.dll_last_address

+

dll_len = self.ql.os.heap._align(len(bytes(data)), 0x1000)

self.dll_size += dll_len

self.ql.mem.map(dll_base, dll_len, info=dll_name)

self.ql.mem.write(dll_base, bytes(data))

self.dll_last_address += dll_len

+

# add dll to ldr data

self.add_ldr_data_table_entry(dll_name)

+ # add DLL to coverage images

+ self.images.append(self.QlImage(dll_base, dll_len, path))

+

self.ql.nprint("[+] Done with loading %s" % path)

return dll_base

@@ -328,6 +333,8 @@ class QlLoaderPE(QlLoader, Process):

self.pe_image_address = self.pe_image_address = self.pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.ImageBase

self.pe_image_address_size = self.pe_image_address_size = self.pe.OPTIONAL_HEADER.SizeOfImage

+ self.images.append(self.QlImage(self.pe_image_address, self.pe_image_address + self.pe_image_address_size, self.path))

This, in turn, provides code coverage for any Portable Executable image loaded by the loader (including DLL dependencies) and will cause each basic block executed to be logged by the block_callback function when tracing is enabled:

def block_callback(ql, address, size, self):

for mod_id, mod in enumerate(ql.loader.images):

if mod.base <= address <= mod.end:

ent = bb_entry(address - mod.base, size, mod_id)

self.basic_blocks.append(ent)

break

I had left this blog on the backburner for a while, and later found that xwings had already added this for PEs in June, so I submitted a PR to add the DLL coverage as well.

Enter the Dragon (Dance)

The defacto standard for visualizing code coverage in IDA Pro and Binary Ninja is a plugin called Lighthouse, which I’d highly recommend checking out if you’re reverse engineering using these disassemblers. During my off-time, I’ve been trying to use Ghidra, which has a great disassembler and decompiler, and provides a plethora of features that are missing from IDA Pro. Once you get used to its quirks, it’s a fantastic free and open source software reverse engineering suite. I came across a fantastic plugin called Dragon Dance which provides similar functionality to Lighthouse for visualizing code coverage within Ghidra, and most importantly for this post, supports the DRCOV trace format. It supports a number of built-in references which let you do things like diff traces within the highlighted syntax. Here’s a nice depiction from the README of using the scripting interface with these functions:

In addition to this, Dragon Dance supports fixups, which essentially looks at the coverage integrity within the binary and compares this to instructions which have been disassembled by Ghidra. If these differ, then the plugin will prompt the user to fix these areas which Ghidra missed. Here’s a depiction of this below, also from the README:

Putting It All Together

Now that we have Portable Executable trace coverage, and a way to visualize it within a reverse engineering suite, let’s take a look at an example. Qiling comes with a WannaCry binary which we’ll use to demonstrate code coverage here. First, I needed to follow the build instructions within Dragon Dance, which were very straight forward, in order to build and install the plugin. Once this was done and I had it working in Ghidra, I ran qltool with the WannaCry binary and tracing enabled:

# python qltool run --disasm -c wannacry-trace.cov -f examples/rootfs/x86_windows/bin/wannacry.bin --rootfs examples/rootfs/x86_windows/

[+] Initiate stack address at 0xfffdd000

[+] Loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/bin/wannacry.bin to 0x400000

[+] PE entry point at 0x409a16

[+] TEB addr is 0x6000

[+] PEB addr is 0x6044

[+] Loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/ntdll.dll to 0x10000000

[+] Done with loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/ntdll.dll

[+] Loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/kernel32.dll to 0x10141000

[+] Done with loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/kernel32.dll

[+] Loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/advapi32.dll to 0x10215000

[+] Done with loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/advapi32.dll

[+] Loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/ws2_32.dll to 0x102b6000

[+] Done with loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/ws2_32.dll

[+] Loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/msvcp60.dll to 0x102eb000

[+] Done with loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/msvcp60.dll

[+] Loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/iphlpapi.dll to 0x10351000

[+] Done with loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/iphlpapi.dll

[+] Loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/wininet.dll to 0x1036d000

[+] Done with loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/wininet.dll

[+] Loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/msvcrt.dll to 0x10462000

[+] Done with loading examples/rootfs/x86_windows/Windows/SysWOW64/msvcrt.dll

-snip-

[+] 0x408171 50 push eax

[+] 0x408172 50 push eax

[+] 0x408173 50 push eax

[+] 0x408174 6a 01 push 1

[+] 0x408176 50 push eax

[+] 0x408177 88 44 24 6b mov byte ptr [esp + 0x6b], al

[+] 0x40817b ff 15 34 a1 40 00 call dword ptr [0x40a134]

[+] 0x1039c18e 8b ff mov edi, edi

InternetOpenA(lpszAgent = 0x0, dwAccessType = 0x1, lpszProxy = 0x0, lpszProxyBypass = 0x0, dwFlags = 0x0)

[+] 0x408181 6a 00 push 0

[+] 0x408183 68 00 00 00 84 push 0x84000000

[+] 0x408188 6a 00 push 0

[+] 0x40818a 8d 4c 24 14 lea ecx, [esp + 0x14]

[+] 0x40818e 8b f0 mov esi, eax

[+] 0x408190 6a 00 push 0

[+] 0x408192 51 push ecx

[+] 0x408193 56 push esi

[+] 0x408194 ff 15 38 a1 40 00 call dword ptr [0x40a138]

[+] 0x103b00f1 8b ff mov edi, edi

InternetOpenUrlA(hInternet = 0x0, lpszUrl = "http://www.iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.com", lpszHeaders = 0x0, dwHeadersLength = 0x0, dwFlags = 0x84000000, dwContext = 0x0)

[+] 0x40819a 8b f8 mov edi, eax

[+] 0x40819c 56 push esi

[+] 0x40819d 8b 35 3c a1 40 00 mov esi, dword ptr [0x40a13c]

[+] 0x4081a3 85 ff test edi, edi

[+] 0x4081a5 90 nop

[+] 0x4081a6 90 nop

[+] 0x4081a7 ff d6 call esi

[+] 0x10387b49 8b ff mov edi, edi

InternetCloseHandle(hInternet = 0x0) = 0x1

-snip-

A few options to make note of that are passed to qltool:

--disasmprovides the disassembly of all executed instructions-cprovides the DRCONV output trace file path

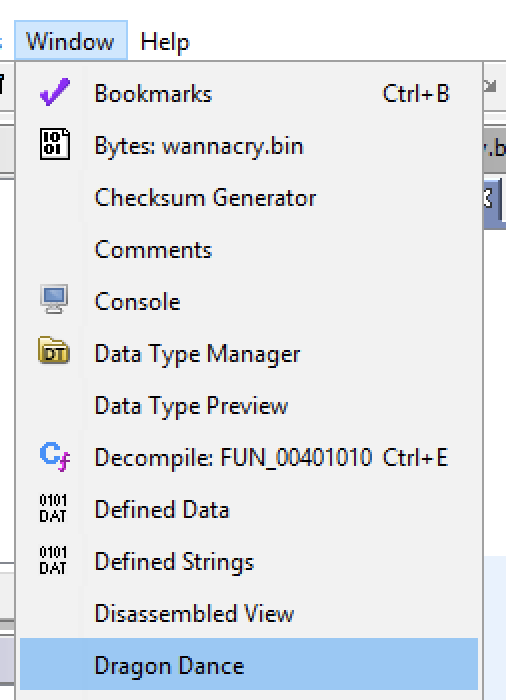

As you can see, the infamous killswitch URL hxxp://www.iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea[.]com was passed to InternetOpenUrlA within our emulation run. Now, let’s import this trace into Ghidra using Dragon Dance and see what it looks like. Once the plugin is installed, we can open the plugin window from the Window dropdown within Ghidra:

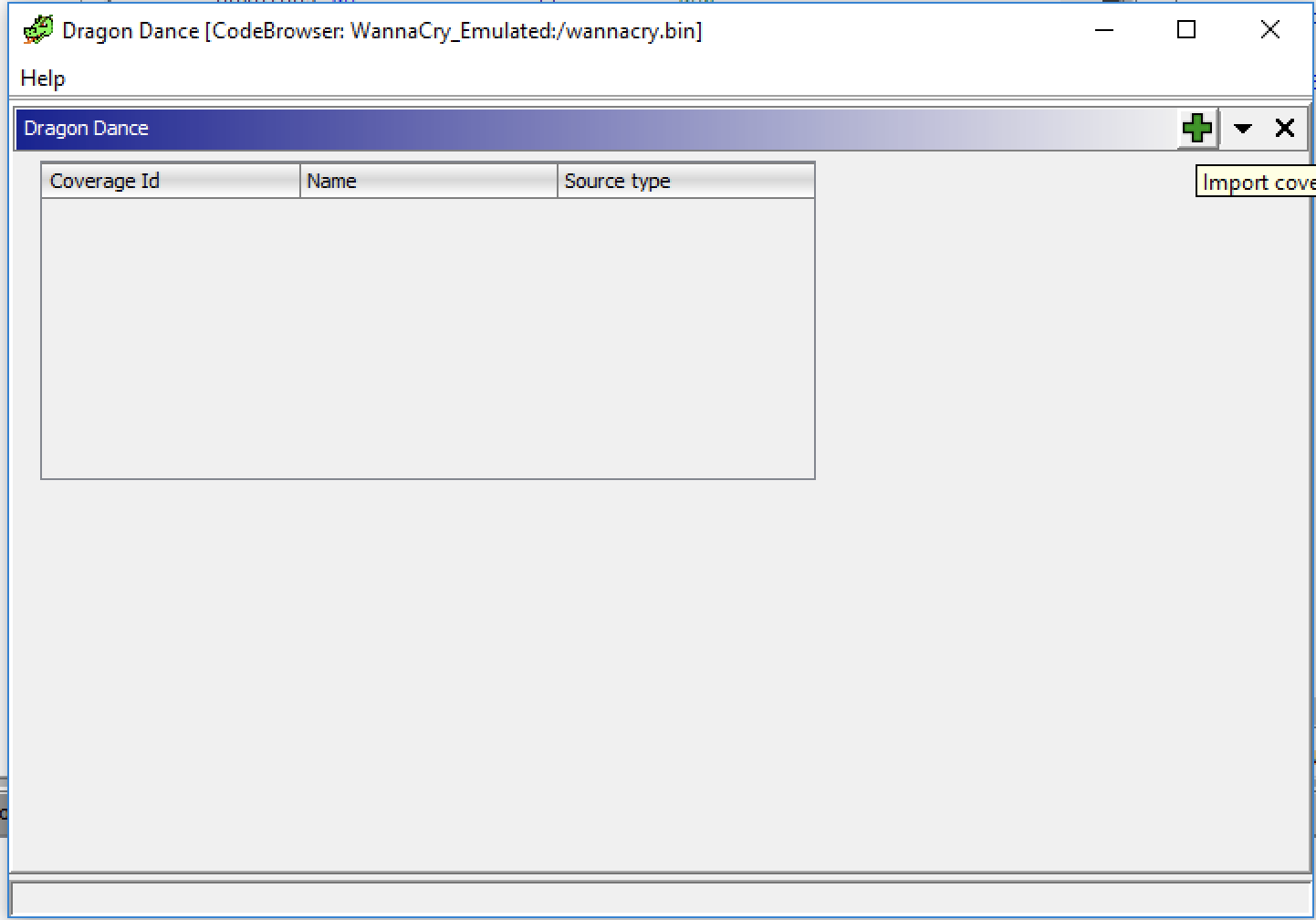

Once the Dragon Dance window is open, we can add a trace file using the green + button:

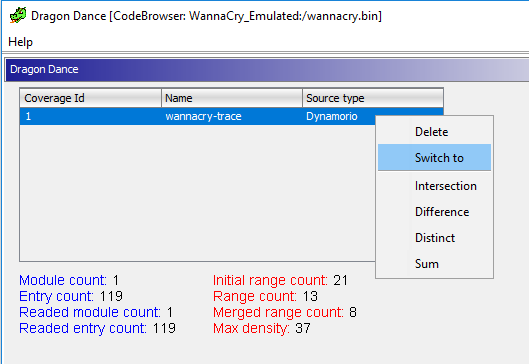

Once added, we can switch to this trace by right clicking on the trace file and clicking Switch To:

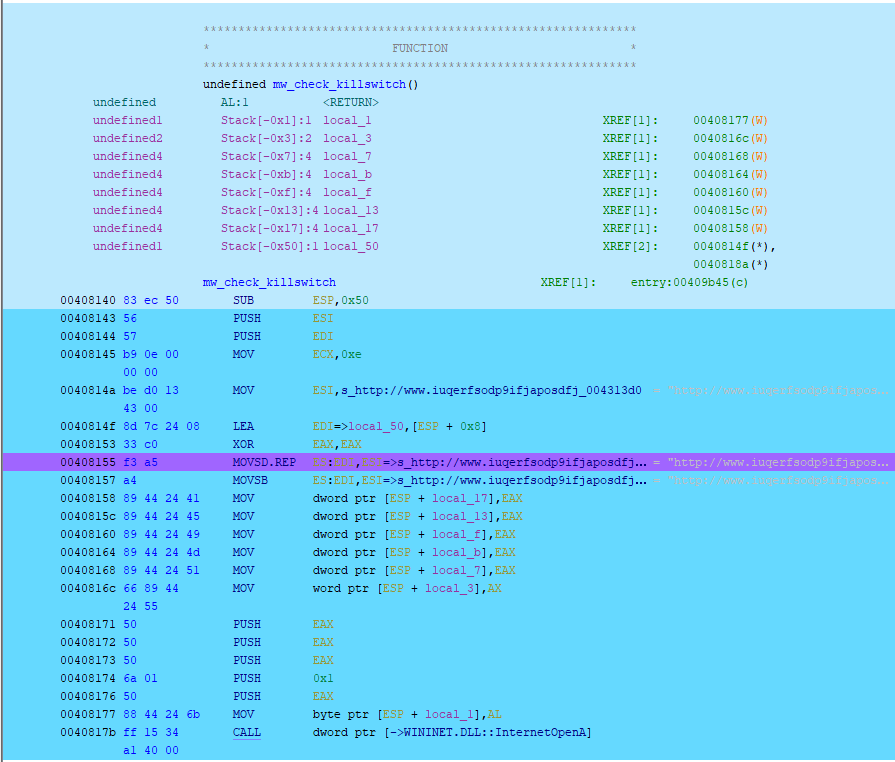

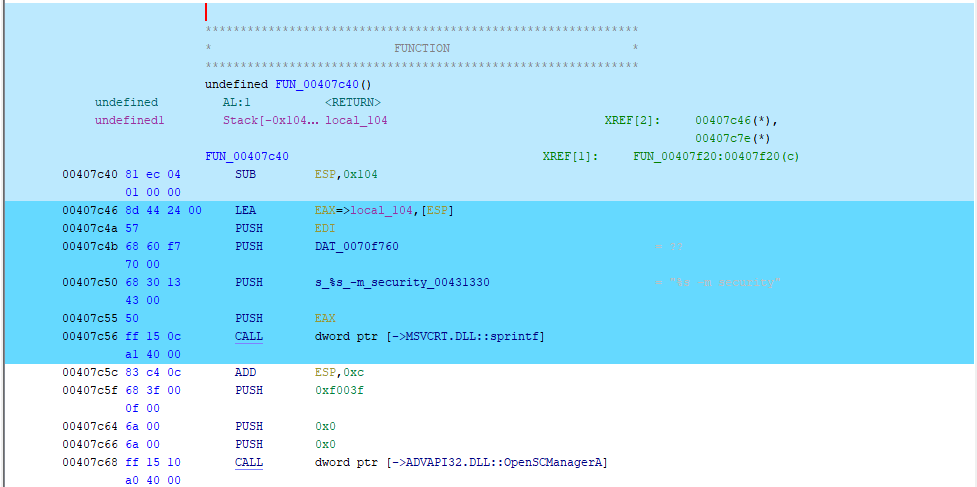

Once applied, all executed/emulation areas of the binary are now highlighted. Here we can see the killwitch function that is called by the WannaCry binary:

If you’ve followed along you’ll see that the emulation of the WannaCry binary dies within the sprintf function:

[+] 0x4080a5 ff 15 2c a1 40 00 call dword ptr [0x40a12c]

[+] 0x104b5aa9 b8 e4 30 ff 6f mov eax, 0x6fff30e4

__p___argc() = 0x5053d44

[+] 0x4080ab 83 38 02 cmp dword ptr [eax], 2

[+] 0x4080ae 7d 09 jge 0x4080b9

[+] 0x4080b0 e8 6b fe ff ff call 0x407f20

[+] 0x407f20 e8 1b fd ff ff call 0x407c40

[+] 0x407c40 81 ec 04 01 00 00 sub esp, 0x104

[+] 0x407c46 8d 44 24 00 lea eax, [esp]

[+] 0x407c4a 57 push edi

[+] 0x407c4b 68 60 f7 70 00 push 0x70f760

[+] 0x407c50 68 30 13 43 00 push 0x431330

[+] 0x407c55 50 push eax

[+] 0x407c56 ff 15 0c a1 40 00 call dword ptr [0x40a10c]

[+] 0x1047f354 8b ff mov edi, edi

[!] sprintf Exception Found

[!] Emulation Error

-snip-

File "/qiling/qiling/os/windows/windows.py", line 115, in hook_winapi

raise QlErrorSyscallError("[!] Windows API Implementation Error")

qiling.exception.QlErrorSyscallError: [!] Windows API Implementation Error

Below we can see no further instruction highlights in Ghidra after the call to sprintf within msvcrt.dll:

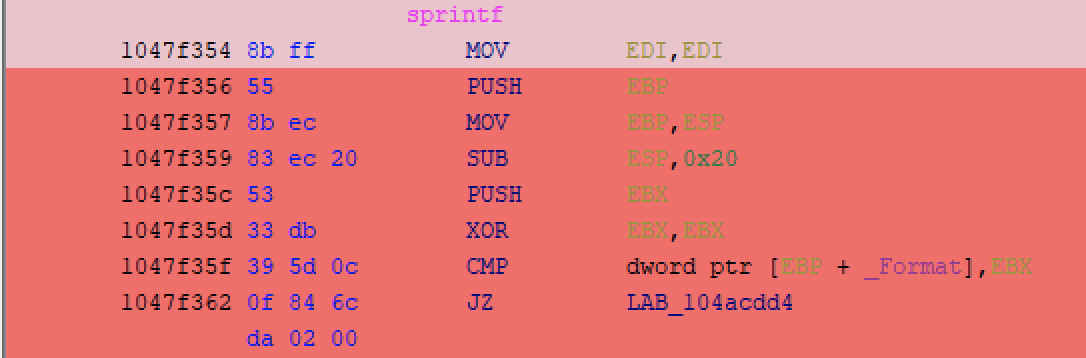

We can, however, visualize the code coverage within the msvcrt.dll dependency itself using Dragon Dance, which is where the exception occurred:

There is a limitation that I ran into though, since Qiling executes blocks of machine code with Unicorn. If an exception occurs while executing a given block (which is the case here) then it might not hit the logging callback once it produces an exception. The visualization, however, still gives you an idea of where the issue is occurring. If we wanted the binary to continue executing, we’d have to take one of two approaches:

- Figure out why execution is failing within the library function

sprintfwithinmsvcrt.dllwhich is resulting in theWindows API Implementation Error - Implement the API ourselves within Qiling so it is supported

The former requires reverse engineering of a Windows DLL, where the latter requires us to work out what sprintf does and implement it within the Qiling framework.

Conclusion

This is a basic example of debugging emulated output, since it’s obvious from the qltool output what is happening, however, being able visualize execution paths for more complex binaries is invaluable, since many branches can be taken to get to a certain function where an error or undefined behavior may be occurring. The Qiling framework is being actively developed and I see updates from it on Github almost daily. The core developers have done a great job at maintaining the project, and I’d suggest using techniques like these to debug APIs and contribute to the project.

Happy Hacking!